Passing the torch

Published 3:31 pm Wednesday, November 10, 2021

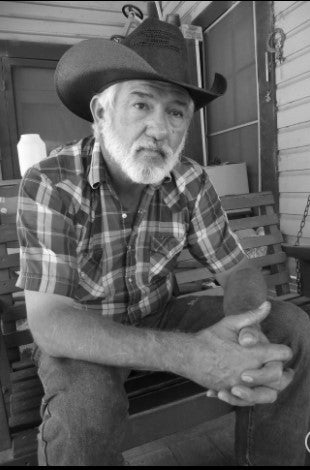

- Edwin Mitchell

By Haley Mitchell Godwin

“In Flanders Fields” has flown from my father’s wise lips and graced my receptive ears many a time. He had to learn and recite the poem in sixth grade.

I am sure that the profound meaning behind the poem and the unparalleled feelings it evokes, in some way contributed to his fondness of poetry and the cause for which he read me Shakespeare at bedtime instead of Cinderella.

My Daddy may not appear to be the poetry kind, but when you compare the definition of poetry to my Daddy, his fluent and depictive Southern English, and the balladry he uses frequently to paint vivid imagery in the minds of whomever he comes across, my Daddy is himself, a poet. (This is where he would say I am a poet and didn’t know it.)

Poetry

- Words that evoke a concentrated imaginative awareness of experience or a specific emotional response through language chosen and arranged for its meaning, sound, and rhythm.

As a boy, my Daddy found this poem intriguing. After serving in the National Guard for 15 years and three months, as the days continue to traverse by, as the grandchildren and great-grandchildren grow, as more white appears in his beard, and as our nation seems to continue to crumble; the larks still bravely sing and more emotion is heard in my father’s voice with each recite of “In Flanders Fields.”

Another definition for you.

Veteran

- A person who served in the military, naval, air service, or other armed forces and who was discharged or released therefrom under conditions other than dishonorable

- A person of long experience usually in some occupation or skill

My father says he is not a veteran, but it takes many moving parts to keep our armed forces operating strong. He was once a contributor to that effort like so many soldiers that did not see wartime. Your service is appreciated.

And for definition number two, the longest occupation any of us has held is that of being a human. As the poem says, breaking faith to our fellow humans that have gone on, will provide no peace for those that came before us. Fulfilling our occupations as humans can only be done successfully if we build on any progress past generations have made and try harder to correct any wrong turns taken.

The torch of hope mentioned in the poem still shines brightly as a symbol of hope, an emblem that may be needed now more than ever. The poem depicts the sacrifices made by soldiers and serves as a beckoning for the living to press on. The poem is a reminder of warfare and of death, and of the transition between the struggle of life and the peace that follows. (Xanax)

The torch of hope is not only for soldiers, but for proud Americans, all Americans, and all people. It is ours to hold high in all aspects of life here in the land of the free and the home of the brave. We must only take actions and speak words, that improve all situations and enhance all elements of existence for every human. Lift others up and never contribute to bringing anyone down. It is only then; we will progress as a nation and as the human race.

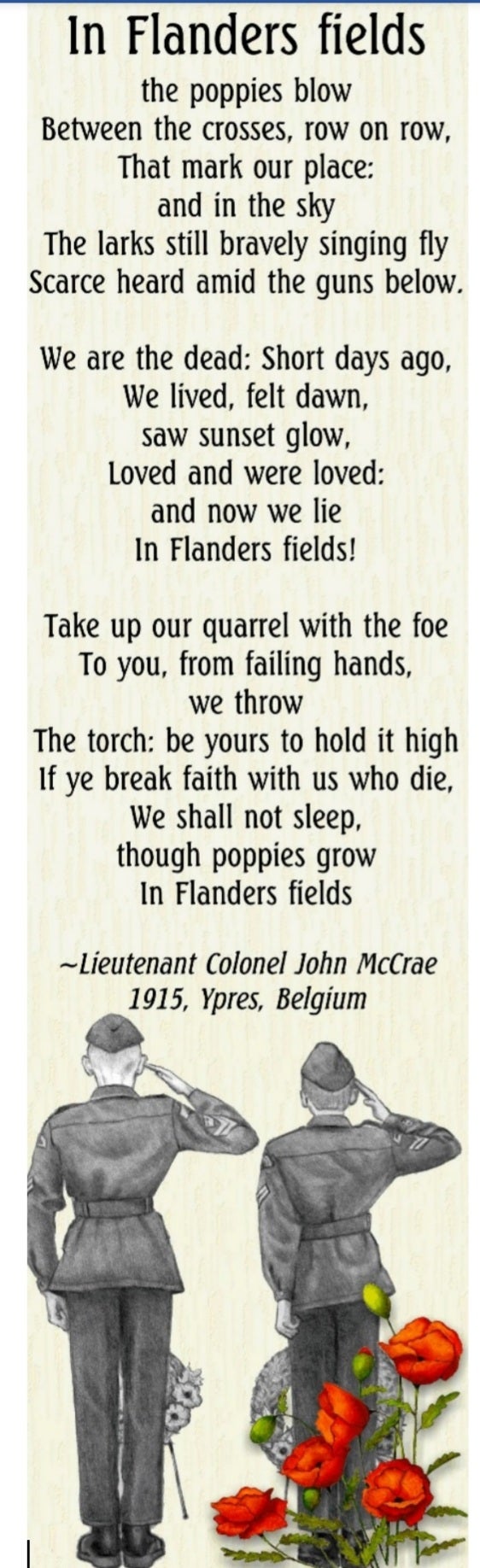

So, where did such a poignant poem come from?

Early on the morning of May 3, 1915, John McCrae sat wearily near his field dressing station, a crude bunker cut into the slopes of a bank near the Ypres-Yser Canal in Belgium.

The author of “In Flanders Fields”, John McCrae, was a Canadian military surgeon in WWI. He had been at the French line for 12 days under ceaseless German bombardment, and the toll of dead and wounded was appalling to the soldier.

From his position beside the canal that ran into Ypres, McCrae wrote: “I saw all the tragedies of war enacted. A wagon, or a bunch of horses or a stray man, would get there just in time for a shell. One could see the absolute knockout; or worse yet, at night one could hear the tragedy, a horse’s scream or the man’s moan.”

The previous night McCrae buried a good friend, Lt. Alexis Helmer of Ottawa. Helmer had been blown to pieces by a direct hit from a German shell. As McCrae was sitting in the early morning sunshine, he could hear the larks singing between the thundering of guns and cannons. At a nearby cemetery, the morning sun shown brightly on the crosses.

The cemetery was in a field of scarlet poppies. Their dormant seeds had been disturbed by gunfire and the digging of so many new graves. The poppies bloomed in spite of the carnage, or perhaps because of the butchery.

McCrae digested the scene that lay before him and quickly wrote the 15 line poem. In Flanders Fields came to be known as the Great War’s most notorious poem, but the volumes that McCrae’s words speak are forever applicable to the cataclysm of war.